With all that has happened in London in the last couple of weeks Will Eisner’s last work has gained a kind of relevance that he did not intend- it does after all deal with a specific theme- but sharpens into focus how humanity, for all its advances, still has an intense suspicion and dislike for what it does not understand, and has a deep-rooted fear of what could be disturbingly called “the other”.

The Protocols of the Elders of Zion is a particularly insidious, inflammatory tract that supposedly details how a secret cabal of Jewish leaders plotted to take over the world and how they would accomplish this. The Protocols have been used across the globe to prove how sinister, cruel and downright devious the Jewish race is. The Nazi Party seized upon it as one of the foundations of Nazism when Hitler made a pointed reference to it in Mein Kampf. The BNP in this country make wide-spread use of it, as do the Klu Klux Klan and extreme right-wing groups in America. It has found a vast audience in the East, especially in Arabic countries and Palestine and yet, for all that it contains purporting to be the facts and its use as an excuse for anti-Semitism, not one word or sentence is true. The Protocols of the Elders of Zion is one of the biggest frauds, and defamation upon a race of people ever wrought upon the face of the planet.

The Plot is Eisner’s attempt to lay this vampire of a tract to rest. I will point out from the very beginning that sadly, of course, he will not succeed. As he details in the book, the “Protocols” have been denounced as fake for a very long time, indeed practically from the moment it first appeared in 1905. Esteemed papers such as The Times of London, L’Express and the Washington Post to the United States Senate and even in a lawsuit against the Nazi Party where they could not find one person who could prove that the “Protocols” were genuine have nailed stakes into it time and time again. So why does it keeps on appearing, never changing and always being published somewhere? To Eisner, this is the real crux of the story.

Eisner’s parents were American-Jewish immigrants. They were neither Orthodox nor Reformed, but they did “believe” and as Eisner grew up during the Great Depression- experiencing painful incidents and indignities- he remembered being angry at his parent’s shtetl attitude, who advised him to “be quiet and not offend the goyim”. He was a student with radical inclinations during the 1930s and became interested in the devices that anti-Semites used to promote their message, but it was only till later in his life that he actually came across an English translation of the “Protocols”. He had been thinking about a graphic novel detailing some of the best fakes of the twentieth century, but after reading it he knew that the “Protocols” was the story and that the premise that runs through it and the whole history of the human race was simple: – whenever a group of people are taught to hate, a lie must be formed to inflame that hatred. And the target is always easy to find because the enemy is always the “other”.

The real author of the “Protocols” intended for it never to be used in the way it has or against the Jewish race, in fact his target was Louis Napoleon- Napoleon III. Napoleon III’s reign was not a particularly happy or safe period. He tried to regain France’s prestige through military adventurism which came to an inglorious end when he declared war on Germany whereupon the French were swiftly defeated.

Maurice Joly was a French radical who wrote many caustic essays on French politics of the time and he joined other severe critics of Napoleon III, who regarded him as a ruthless despot. In 1864, Joly wrote a book called “The Dialogue in Hell between Machiavelli and Montesquieu”. It was intended to liken Napoleon to the infamous Machiavelli and reveal the French dictator’s dark and evil plans. The book saw publication, but it caused nothing but trouble for Joly after. It was originally published in Belgium and then started to appear in France. Joly was arrested for distributing a forbidden book and sentenced to jail. In 1878, he committed suicide and the book was left to be forgotten.

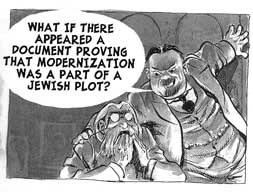

In 1894 Nicholas II was crowned Tsar of Russia. He had very little experience in affairs of state and was on the whole a dull, reactionary and ineffective ruler. Although revolution was already stirring in Russia, Nicholas authorized a series of pogroms against the Jews in order to maintain a resemblance of order. Such things had happened before, but Nicholas was an easily persuaded man and at the time his most trusted advisor was Sergei Witte. Witte advocated closer links with the West, which was against the feelings of the more Conservative court dominated representatives. The Tsar was all for the links to be established, but feared that the West would not look too kindly upon his pogroms. Witte proffered the view that the Tsars view of the Jews was the same in the West (an altogether not untrue statement), but his views on modernization brought Witte enemies. Gorymikine and Rachovsky in particular, and they were associated with secret police. Taking both Witte’s and the Tsars views upon the Jews they devised a scheme in which if it could be shown that modernization was a Jewish plot the Tsar would quickly back-pedal, but how to do it? Enter the plagiarist and faker Mathieu Golovinski.

Golovinski was from an impoverished, aristocratic family and was politically corrupt from the start. He played both sides, working as a clerk for the state police and organizing street protests at the same time (though making sure he was never found out). Under the protection of Count Dashkov, he faked many false documents that sent men to the gulags and it was Dashkov that referred Golovinski to Soloviev, a member of the Holy Synod. Under Soloviev, Golovinski faked and fabricated press articles denouncing the Jews and their plots to undermine Russia. In Russia religion and politics were the same, but Golovinski cared nothing as long as he was being paid well. In time Soloviev died, Golovinski and his conservative writings fell out of favour with the court and he was accused of provocation and being an informer. Given the choice of Siberia or exile he took the road to France and started work for the Franco-Russian League, an off-shoot of the Okhrana. At the same time Rachkovsky appeared in Paris looking to find his inflammatory document. Reporting to the Okhrana, Rachkovsky set about making up the document that could persuade the Tsar that there was a Jewish plot against his throne. Introduced to Golovinski as one of their best forgers he gave the job to him to be done within 30 days, a seemingly impossible task. The Dreyfus affair was making all the news at the time in Paris and Golovinski was also informed that in 1897 a meeting of leading Jews in Basel had advocated a Jewish state, but there was nothing to support anything that could be seen as a conspiracy. Time was running out for Golovinski when someone, maybe Rachkovsky, introduced him to Maurice Joly’s “Dialogue”. It was perfect. Joly’s attacks on Napoleon could be read as a plan for tyranny, and with changes that made sure that it looked as if it had emanated from Jewish leaders it had all the hallmarks as a conspiracy and a weapon. The stage was set.

The “Protocols” were first published in Russia by one Sergius Nilus, a would-be mystic and competitor to Rasputin. The book was entitled “The Great in the Small” and parts of it were given over to the “Protocols”. Nilus would not say where he had received the document from, only that he had been given it from the Okhrana and he was sure of its truthfulness. Members of the court were less convinced but it did not matter, the Tsar believed it. Witte was out and anti-Jewish pogroms were rampant. It was widely circulated and monarchists frequently read it aloud to illiterate peasants (a chilling parallel to today, with radical Imans reciting anti-Western literature in many poor villages in Pakistan). With the onset of the First World War, and many Russian military defeats, loyalists openly spoke of a “Jewish plot”. The Revolution brought about the downfall of the Tsar and his execution. Many aristocrats fled Russia, settling throughout Europe, the Far East and the Middle East. With very little work experience the frequently sold valuables. Some of these provided information on the Russian use of anti-Semitic literature.

All this happens in much more detail in only the first half of Eisner’s book. Over a long period Eisner stopped using the atmospheric use of shadows and black ink that characterised his work on The Spirit and started more of a wash. This is used to superb effect in The Plot. The black and white wash along with character mannerisms both subtle and exaggerated conveys a sense of discomfort and historical fascination at how easy it is to create and use such a hateful document, but Eisner has only just started. To prove that the “Protocols” are fakes was the easy part (if involving long trawls through a lot of data); to explain why they continue and are still in use is much harder.

The Times of London, 1920, was the first paper in the West to draw attention to the “Protocols”, denouncing them as anti-Semitic. But the story grew in the telling; drawing such luminaries as a young Winston Churchill and Henry Ford into believing them (Ford had bought a small newspaper which was distributed amongst his workers, and later published world-wide. “Borrowings” from the “Protocols” were included. Ford later recanted in 1926 when he was about to be sued for libel). In 1921, a Times writer named Philip Graves was approached in Constantinople by a Russian émigré who had documents and a copy of Joly’s book that could prove that the “Protocols” were fakes. This whole chapter of the book is then given over to comparing both them and Joly’s work, with interpretations from both and Graves (Eisner) showing the similarities. By the end the conclusion is obvious, the document was a fake and The Times said so loudly (pity the Times couldn’t be a little more rigid decades later when they started to publish the Hitler Diaries. They’ve never been able to live that down). Unfortunately, at the same time in Germany Hitler had started his rise to power and was extensively using the “Protocols” for his own ends. The Nazi Party knew that the document was faked, but it didn’t matter. As with pre-Revolutionary Russia, the country was a mess and someone had to be blamed. In Bern 1935, the “Protocols” first came under fire in court. The Jewish community was suing the Nazi Party for the distribution of it and the verdict was clear, it was a fake. You may think that with the Allied discovery of Goebbels’diary, stating that it was useful propaganda, again with the U.S. Senates report in 1964 that condemned it, or with the “Protocols” finally returning home and a high-ranking Russian court saying that they were fakes, the “Protocols” were dead and buried, a relic from an ignorant past. Unfortunately they are not.

In Europe during the 1920s and 1930s, the “Protocols” were just a little bit less popular than the Bible. There is not one anti-Semitic group that has not used them in some way, and it is because a lot of its adherents knew of its origin that they have tried to muddy and obfuscate its beginning. The document is still wide spread across the world, even more so with advent of the internet, but the authenticity of the work doesn’t matter to those who believe it. The anti-Semite, according to Jean-Paul Sartre, “turns himself to stone”. Bigotry becomes their way of explaining the world without recourse to logic or facts. Anti-Semitism (or anti-Western, or anti-Islam) is a convenient worldview for those who feel threaten by the modern age, or the future, and those who seek comfort in rigid religious and anti-democratic forms of authority. Eisner explains this in a fictional meeting with his younger, more radical self; the “Protocols” are nothing more than a weapon of mass deception (?) In all cultures there are those who wish for political power, and what easier way to gain it by then identifying a felt threat to the people and leading a defence. Fear of the “other” and impact that “they” could have on a way of life has led to the world that we all now inhabit. In the end, the “Protocols” are irrelevant, a bogey to be used as and when it suits, far more disturbing are the motives behind such documents.

Eisner’s book is an important one, and should have received a lot more media coverage than it did (the literary section of the Sunday Times and Newsnight Late Review totally ignored it, preferring to bitch or rave about something as insubstantial as Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince). It was Eisner’s last work before he died and is a fitting end to a career that turned the whole of the comic book genre upon its head. Like Schulz, Eisner believed that the idiom should be used to entertain and inform not preach and with The Plot: The Secret Story of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion he succeeds admirably. Will his tale last longer than the “Protocols” themselves? Sadly the answer has to be no. By the end of his tale, Eisner has realised that human nature will not change, that even if something has been proved to be false time and time again the lie will always suit someone’s view and rise, vampire-like, no matter how many times it gets staked. I thoroughly recommend the book as both a piece of documentary and historical writing, it may be slender compared to something like Jung Changs “Mao” or Simon Schamas “History of Britain” but its importance is comparable.

The Plot: The Secret Story of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion is by Will Eisner (with an introduction by Umberto Eco), published in hardback by Norton and priced £12.99.